Guerrilla Groups

"What unites us is the resolute decision to fight and our eyes are always set on the great objective of achieving a bright future of peace and freedom in our fatherland" – A Salvadoran Guerrilla

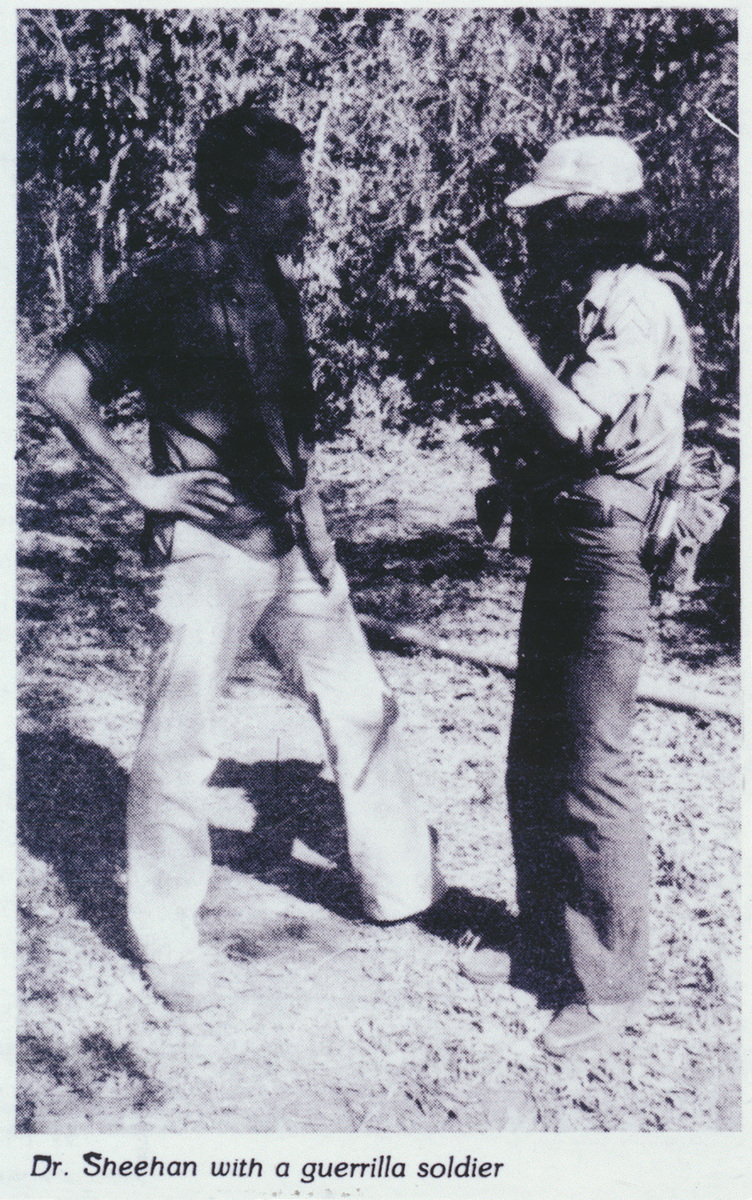

During the 1970s, many factions of armed resistance against the Salvadoran government formed. These groups combined political organizing of the peasantry with military tactics to stop the Salvadoran military from exacting absolute power. Taking to the countryside, those who were once coffee farmers and cotton growers became guerrilla soldiers. Guerrilla warfare worked in tandem with the other non-violent methods of political organizing to diversify the ways in which ordinary Salvadorans challenged their government.

Among the various resistance groups, the PCS (Communist Party of El Salvador), FPL (Popular Liberation Forces), PRTC (Central American Revolutionary Workers’ Party), ERP (Peoples’ Revolutionary Army), and FARN (Armed Forces of National Resistance) emerged as key players throughout the 1970s.

By 1980, these five groups organized themselves into the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN), named for one of the victims of La Matanza. Although they formed a cohesive unit, these groups had different origins, either in Marxist political organizations or in popular youth movements. Although differences between organizations proved challenging at times, the FMLN eventually became the strongest guerrilla army in Latin America during the Cold War.

Revolution did not just occur in opposition to the military, though. On the other side of the spectrum, a military-civilian coalition known as the Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno (JRG) overthrew the dictator at the time, General Carlos Humberto Romero, in the hopes of weakening the oligarchy and instituting land reforms to benefit the peasantry. While this coup d’etat promised the inclusion of more democratic principles into Salvadoran politics, it only forced the armed groups to work harder in the hopes of achieving power of their own. As 1980 ended, it became clear that the tensions between the government-military alliance and the FMLN would not resolve themselves without civil war.